Beyond Pros and Cons — Start Teaching the Weight and Rate Method

Critical Thinking and Decision Skills are best learned by students when they are explicitly taught. Teachers can (and should) actively seek opportunities to name, explain, demonstrate, and praise student performance of the specific skills and use of the concepts involved in critical thinking and decision making. These skills do not generally develop without such direct instruction. One simple and powerful decision skill you can teach students is the Weight and Rate Method for making a significant (deliberative) decision. I explain the process with a real-life example below. Please let me know in the comments if you have any questions or suggestions. I wish I had learned this in school. — Joe

How to spend Spring Break?

A few weeks ago a young cousin shared that she was struggling with a significant decision. She was trying to decide which of several ways to spend the Spring Break of her Senior year at Villanova University. As she saw it her choices were a service trip to Peru where she would work as a nursing assistant in a clinic; travelling to Ghana to work in a community making house calls to teach basic health to new and expectant mothers; or to go to Italy with her choral group to sing at several venues, including an audience with Pope Francis. She was wondering how to decide… Her parents had recommended that she use a Pros and Cons list, but she found that there were many pros for each alternative, few cons (beyond costs), and she wasn’t any closer to knowing what to do.

This isn’t a sad story, it’s not a cry for equity or reform for justice. This is just a typical example of the kind of decision that many young people face, much like picking a major, choosing a job or career, deciding where and with who to live, etc. Life presents us with many consequential decisions. Some are about avoiding major errors; drinking and driving, illegal drug use, teen pregnancy, and the like, and those are usually best addressed with norming the “right” choice, and managing the context of people’s lives so that they are less likely to make major choices that will derail their flourishing. For the multitude of other choices though, like whether and whom to marry, if and when to have children, how and how much to save for retirement, whether and where to buy a house, or a car, whether to go with surgery or chemotherapy, and countless others, avoiding bad choices isn’t sufficient. We need decision skills. Yet, if you ask young people what they learned about making significant decisions in school they usually will tell you that they never learned anything about how to make decisions. That seems like something we should change. Our decisions, how we choose and set goals, solve problems, pursue plans, and update our beliefs are fundamental and teachable skills. The fact that we don’t yet teach them to every young person is just a strange artifact of our schooling system. Critical Thinking and Decision Skills are teachable, and deliberate practice makes us better.

Staying with the example of my cousin, she would have been helped by direct instruction in one of the most basic techniques of decision making, the Weight and Rate Method.

I think we should starting teaching every high school student the Weight and Rate Method. The method goes by several names, including “table”, decision matrix, or “decision worksheet” but it is the method, not the name, that matters. The method includes framing the decision clearly and concisely, reflecting on goals and values, creating alternatives, listing criteria, imagining consequences, etc. Here are the steps:

- Name and frame the decision

First and foremost you must realize that a decision needs to be made, and then you must define the decision. Is Emily deciding between three trips, or deciding how best to spend Spring Break? Is she deciding how best to serve people on a trip, or how best to enjoy and remember her Senior Year? The frame matters. Thinking about the decision frame and trying out a few different ones will help generate alternatives and foreground considerations or criteria that might have otherwise gone unnoticed.

2. Generate Alternatives

Come up with several, yes, it really should be more than two, alternatives. If you only have two alternatives, go back and reconsider the frame. Some people, including me, are tempted to skip to the next step, listing considerations or criteria, but the order matters. This is a creative step, generating alternatives, and as we all know from brainstorming exercises, you don’t want to be judging and analyzing when trying to be creative. Emily was starting off with three alternatives, but during this step, we came up with a few more, including combinations where she traveled to Italy to sing with her group and volunteered locally at a clinic.

3. List the Criteria

Start by just listing considerations, things that are meaningful. For Emily some of the considerations were; memories with friends, experience for her resume as a prospective Nurse, international travel, costs, safety, access to emergency care, and opportunity for service to others. If you’ve been thinking and following along, but not writing things down, here’s where you’ll get lost. We have limited memories and can only mentally juggle a few ideas at a time. By writing down our criteria, we not only clarify our thinking, but we also increase the number of criteria we can include in our decision making. This stops us from jumping from one (or a few) to others and lets us organize our deliberation.

4. Reflect and seek input

You have a decision named and framed, you’ve generated some alternatives, and you have a list of criteria you are considering. Now is a very good time to talk with trusted advisors, experts, and others with experience and wisdom around this type of decision. Emily asked her parents, a faculty advisor, and her friends for their ideas. She was able to listen and ask questions and maintain her boundaries that this was a decision she would be making later, not during the conversation with them, but was seeking their counsel so as to improve her thinking about the frame, alternatives, and considerations.

5. Loop

Go back to your frame, alternatives, and criteria and make any changes you think advisable. Don’t get lost in the looping. The purpose here is to make a good decision, not to wait for the perfect answer to reveal itself. Once you’ve written down your updated versions, move on.

6. Assign Weights

Set aside your alternatives for a moment. This is the step where you give weight to the factors you’ll use to make your choice. Not every criterion is of equivalent value to you. There are many different approaches to this step of the method, but my preferred approach is to start off giving everything 10 points, up to a maximum of 100. (If I have more than 10 criteria I use 5 instead to start for each).

Now reassign the points to reflect your valuation of each criterion.

This step usually takes some time, so take it. Mess about a bit with the numbers and get your preferences down on paper. Don’t be afraid of the numbers, they are your friends. They will expose your feelings on thinking about the relative value of the criteria.

7. Build a Weight and Rate Table

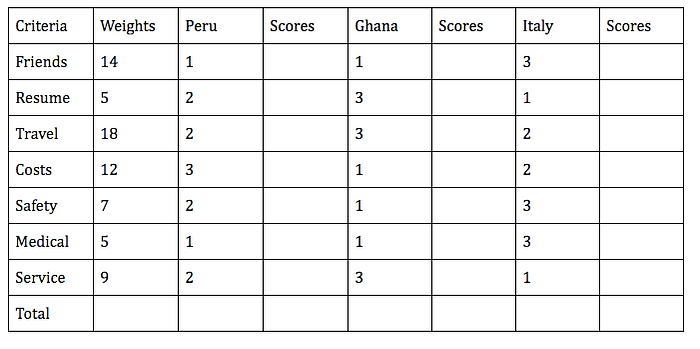

I prefer to do this in a spreadsheet, but doing it by hand is just fine, and probably how I would teach it to students the first time. The top row lists the column headings: Criteria, Weights, Alternative 1, Scores, Alternative 2, Scores, Alternative 3, Scores, etc. Now, it’s time to think about the weights. I am in the camp of using 3 possible values (1 — low, 2 — medium, 3 — high). Some people prefer to use negative and positive values, but I find that confuses too many students. Start simple. You can always get more sophisticated. If you are using all positive values; low, medium, and high, then a high score means a high good rating. For example, Emily expected a stipend from the nursing program to help pay for the trip to Peru, reducing the costs, making it preferable. This means she would score Costs for Peru “high”, a “3”.

8. Calculate

Calculate the scores for each alternative by filling in each cell of the table. The Score for Peru in the Friends row would be the weight for Memories with Friends (14) multiplied by the rating for Peru in that row (1). So 14 X 1 = 14. Try to complete the “Resume” score for Ghana. If you wrote “15” you seem to have the process down. Just complete the table. Once you are done calculating each row, sum the scores column for each of the three alternatives.

9. Reflect

Surprised? I was. I expected it to be close between Peru and Ghana, so did Emily. However, once she listed her considerations, gave weights to her criteria and scored each alternative the picture was already becoming clearer. The trip to Italy, singing with her friends was the clear winner. The calculation drove home her best option as well as demonstrating to her the value of the method. Emily’s relief at having a clear decision that was aligned with her preferences (values in decision science speak) and her judgment regarding each alternative at the decomposed level of the criteria was obvious in the tone of her voice and body language. She had a decision and felt good about the process. That might not have been the case. She might have felt something was wrong. But that would have been helpful too. If you go through this process and something doesn’t feel right, then you probably have either used the wrong frame, left out criteria, or assigned weights that aren’t aligned with your real preferences. That’s okay! This is your decision. Go back and re-work the steps and see what you think should change.

In the rare case that everything feels right, but you still have a tie between two or more alternatives, that’s okay too. That means you are likely to value the various outcomes similarly and you can stop worrying. Just pick one and move on. You’ll get different results, but you value them equivalently. This is rare though, usually, a tie will cause reflection revealing a criterion or weight you didn’t know consciously that you had and the best alternative will be revealed.

10. Decide

What does it mean to decide? At its most basic, it means to choose among alternatives. Emily’s choice was clear, she’s going to Italy. Deciding for her means taking the necessary actions to see that decision come to fruition; getting a passport, signing up for the trip, paying the fees, and packing her bags. Fortunately, she’ll have lots of opportunities to provide service as a nurse and is very excited to sing this time with her friends in places she has always wanted to see. She’ll also have lots of opportunities to practice deciding with the Weight and Rate Method.

11. Advanced

Here are two techniques for those interested in exploring the method further.

Satisfying the ⅔ Ideal Case

Add a column for “Ideal” the alternative you haven’t thought of yet. Give it an automatic “High” score in each criterion. In our example, Emily’s “Ideal” alternative would have a total score of 210. A good rule of thumb is ⅔. A good decision should score at least two-thirds of the ideal but unknown alternative. That means Emily would need a score of at least 140. Only Italy makes the cut. If she didn’t have Italy among her alternatives, Emily would go back to the drawing board, reframing her decision and getting creative about new alternatives.

Consider the Probability of Success

We sometimes fall into the trap of wishful thinking. When we choose a path that is less than certain to work out as planned we should consider that in our decision making. Try adding an extra row for Probability of Success and assign a value in each scenario for the likelihood from “0” to “1” (40% is .40) of things working out if you make that choice. Then when calculating the total score for each alternative multiply it by the corresponding Probability of Success. Any value less than “1” (100%) will cause the score to shrink proportionally to its likelihood of working out. That means that a seemingly great alternative with a low probability of success might end up less valuable than a pretty good alternative with a high value of success.

Teaching Decision Making and Critical Thinking

I hope that you found this description of the Weight and Rate Method helpful. It just one of many tools and skills that can help each of us become better decision makers. Decision skills are something that we can learn, practice, and improve.

I believe that better lives come in large part from better decision making. Learning and practicing decision skills enables us to maintain physical health and emotional wellbeing; form reasonable beliefs about the world; and pursue wise personal, professional and social goals effectively. That’s why I joined the Alliance for Decision Education, an educational nonprofit dedicated to helping youth become better decision makers.

Our team is working to build the field of Decision Education for Youth. We seek to identify, coordinate, and amplify the efforts of researchers, educators, policymakers, program providers, funders, parents, and thought leaders supporting Decision Education for Youth. The field combines teachable skills, dispositions, content, and behaviors from Critical Thinking, the Science of Learning, the Decision Sciences, Probability, and Social Emotional Learning. We want to hear your ideas about what works and how we can make Decision Education part of every student’s experience. Please join us at www.AllianceforDecisionEducation.org

Warmly,

Joe

Dr. Joseph Sweeney

Executive Director, Alliance for Decision Education

#DecisionEducation